A stroll through Ron Waples' basement in his home near Guelph, Ont., is a walk through his history, as long and colourful as can be.

Woodbine Racetrack opened its doors to the public on June 12, 1956 and will celebrate its 60th anniversary, many decades worth of memorable moments and rich traditions, on Sunday June 12th as the finest thoroughbred fillies in the country compete in the Woodbine Oaks, Presented by Budweiser.

To honour this landmark anniversary, leading up to Oaks day, we will share stories of some of the longstanding names of the industry, both thoroughbred and standardbred, courtesy of Sovereign Award-winning writers Beverley Smith and Bruce Walker. By Beverley Smith for WoodbineEntertainment.Com

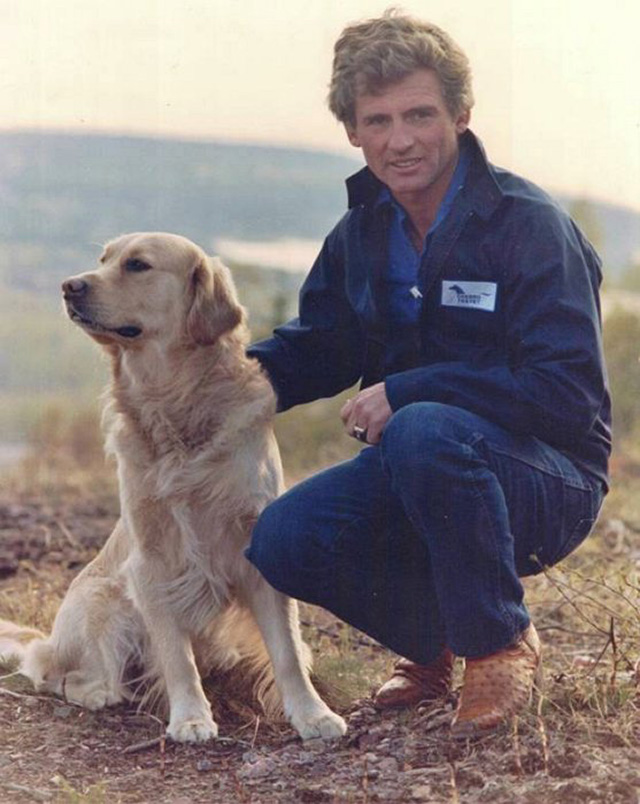

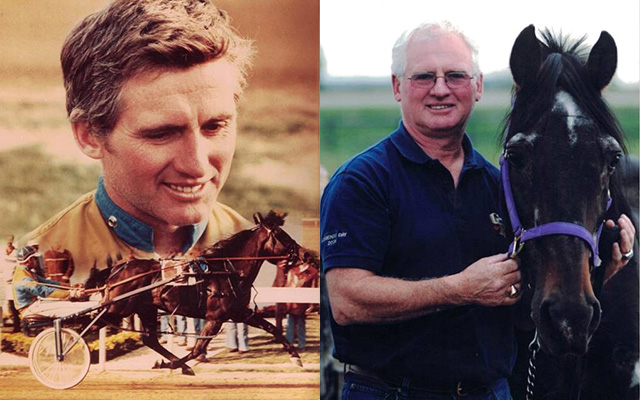

A favourite photo. (Courtesy of Ron Waples)

There's the simple little antique rocking chair, that his mother, Sylvian, used to sway he and his siblings to sleep, painted 50 or 60 times over the years. ("My mother was a painter," Waples says.) There are photos galore. Paintings galore. A metre-high bear carved out of light wood, which has been with Waples for 30 years, from a trip to California. A book on his favourite comedian, George Burns, and a photo, signed by the star. (Waples sent him the book to be signed, and included a photo of No Sex Please, which he thought might inspire Burns to take interest in the request. Apparently, it did. Burns signed the book and sent it back. Much to his chagrin, a decorator thought it best to place it in a washroom. Waples has a name for this room.)

And that's not all. There are native figurines that tickle Waples' fancy with their movement and detail. And a photograph of the entire Waples clan that drove together in promotional races (woe to the announcer, trying to separate them out), all clad in blue and gold. Worse still for the announcer, they all wore muddy faces, too.

The memories are still fresh, the adventures all worth it. Waples, now 71, is still driving in –- and winning -- races, brushing close to 7,000 wins. His most recent victory at Mohawk Racetrack came last fall with a wayward filly, Devils Advocate, from the Jack Darling Stable. He took her on as a project last season and spent months teaching her etiquette.

"She was very nervous, " said Liz Waples, his wife. "She's a handful to hook."

Waples' goal with her had been to get her to walk all the way around the racetrack. Eventually, she did.

Waples qualified the filly and said to Darling: "Whoever you get to drive this filly, hopefully we can tell him to back her off the gate and teach her something."

"You're going to drive her," Darling told Waples, knowing very well that the septuagenarian knew her better than anyone. Waples had been the only person to jog and train her, since starting with Jack in April.

"No, I'm not," retorted Waples, who has driven seldom over the past handful of years, his hands and feet rather arthritic now.

"Yes, you are," Darling insisted.

"No I'm not, I don't drive anymore," Waples said.

"Well, you're going with her."

In the face of Darling's single-minded intent, Waples made a deal with him: "I'll go under one condition. The first time I screw up, we fire me."

Deal.

With Waples driving, the filly won more than $100,000 last year, took two full seconds off the Canadian record for two-year-old trotting fillies on a half-mile track at Flamboro, (all this after a recall which she used to rear up a couple of times in the infield) and then she won a $70,000 Ontario Sires Stakes Gold series race at Mohawk, Waples' first victory at the track in five years.

He returned to the paddock to cheers and applause from his peers, a rare occasion indeed.

Waples might not admit it, as modest as he is, but this applause thing has been going on for a long time now.

The Road Less Travelled

But maybe not quite when he was growing up. He left home when he was 15 years old. He just couldn't get along with his father, Bert.

"I don't want to insinuate that I didn't have a good father," Waples said. "I had a father I couldn't get along with, but that does not make him bad. And I had a real good mom."

Truth be told, Waples was a bit of a rebel when he was young. He hated school. It took him 10 years to get through public school. The only things related to school that he didn't hate were playing baseball, doing gymnastics and arithmetic. "For some stupid reason, I liked arithmetic," he said. "But I got so I even hated school teachers."

His teachers were very nice people, he recalled. Super teachers, in fact. Then he went to high school. He had an English teacher who would get on his case, so Waples would resist him by sliding his desk over to a girl in his class, and putting his arm around her. The English teacher would get flustered. His face would get red.

"I guess I was a bit of a yo-yo," Waples admitted. "I was a screw-up."

To this day, Waples stresses the importance of education to children he meets. He tells them they must finish school, that essentially, they must not do what he did, so long ago. It would have been so easy for him to have taken the wrong path. Years later, a kingpin harness driver and chief of the Central Ontario Standardbred Association, Bill O'Donnell was to say that Waples "could have run IBM. He was that kind of guy.

"He had probably 100 horses at one time, and he'd be at The Meadowlands racing, and hauling horses up here, and telling them where to enter them all," O'Donnell said. "It was unbelievable how he kept all of that in his head."

But the watershed moment in Waples' life came from crossing bows with his father. "He was very intelligent as far as machinery goes," Waples recalled. "Old cars, tractors, combines, anything, he could make them things work. He just had the gift. And he was all for anybody who was ambitious."

"I come up a little short on both ends," Waples added. "I had no interest in machinery. I didn't care if the tractors started or didn't start. I didn't want to know why they didn't start, either. And I was a little on the lazy side, I presume. So it did not work well."

When Waples was 15, he had a confrontation with his father. "One thing led to another," he said. Waples marched to the house and told his mother that he had had enough, that he was leaving.

"Where are you going?" she asked.

"I don't know," Waples replied. "I'm just leaving."

The Waples family lived out in the countryside, about five or six miles from a highway. Waples walked that stretch of country road, not looking back. The previous day, he'd withdrawn every penny from his bank account. "I had "$32 in my arse pocket," he said.

He had a long time to think on that walk. His thoughts were a jumble, but his purpose was absolute.

When he got to the highway, he hitchhiked a ride into Midland –- everybody hitched back then –- and told the driver he was going to see Jack Turner, who had been leader of a Boy Scout troop that Waples had joined as a boy. He loved the Boy Scouts. Waples knew that Turner worked at the post office in Midland. And there he found him.

"What are you doing in town?" Turner asked him.

"I've left home," Waples said.

"What do you mean, you've left home?" Turner said, astonished.

"Just like I'm saying," Waples said. "I left home."

"Are you going to go back?" Turner asked.

"No."

"Well, what are you going to do?" Turner said.

"I don't know," Waples said. "But I'll help you finish up your stuff here."

So he gave Turner a hand. Turner took him home for supper. Turner lived only about five miles from his parents' house.

In the meantime, Turner called Waples' parents and told him where their son was.

"Do you want me to come and pick him up?" Waples' mother asked.

"No, I don't think so," Turner said. "I think I'd just leave him here for a bit."

After supper, Turner put the question to him again: "Are you ready to go home?"

"I said no, Jack," Waples replied. "I'm telling you. I'm not going home. That's all there is to it."

"All right," Turner said. "You see that couch there? You're going to sleep there. And you'd better be there in the morning when I wake up."

"I will," Waples said. "I got no place to go. I'll be there."

Turner asked him what he was going to do next. Waples told him the following day, he'd help him work in the post office. After that, he didn't have a clue.

The choice of a lifetime

On the road to the post office the next day, fate and chance and something indefinable took control of Waples life. To this day, he tells youngsters that you often face highways that split and the decisions you make mould your life.

"You've got the good way," Waples would tell them. "Or the bad way. I was a rebel. I was a pain-in-the-ass kid. I know I was. So it would have been as easy for me to be in jail as not."

He'll always ask kids what their goals are, what they want to be when they grow up. "When I was a kid, I wanted to be a truck driver or a cop," he said. The allure of truck driving had something to do with just wanting to blow the air horn.

But on this momentous trip to the post office a day after he left home, Waples peered out the window and spotted a pasture populated with horses. And that made all the difference. Just the sight of horses. Living, breathing horses, tails switching, manes tossing in the wind.

"I know now what I'm going to do," Waples told Turner.

"What do you mean now, you know what you are going to do?" Turner asked.

Waples, in a flash, had made a plan. He would get himself to Coldwater, Ont. -– north of Orillia -- where his cousin, Keith Waples, trained horses. And he would get a job with him, he told his friend.

"Where did that come from?" Turner asked.

"Well, you see them horses over there," Waples said. "I love horses. I love being around them. I don't care if I never see another tractor in my life."

Waples helped Turner in the post office that day. When Turner offered to give him a lift to his destination, Waples said no, asking only that he drop him off at the bus station. "You've done enough," said Waples, already sounding very mature, gracious really. "I really appreciate what you've done for me."

The University of Keith Waples

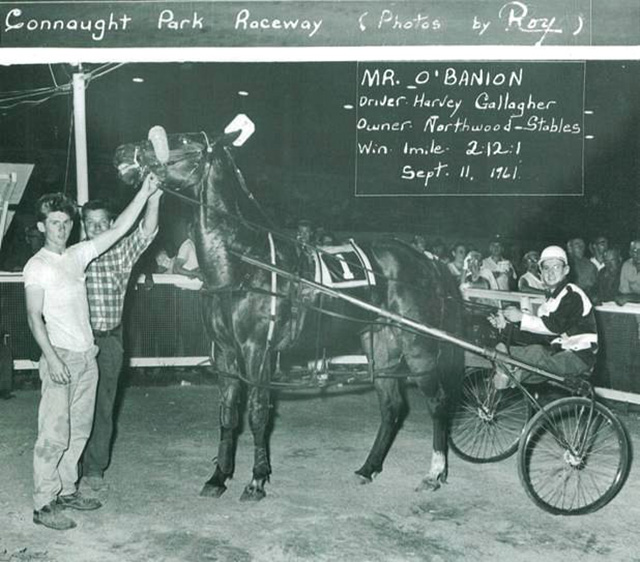

A young Ron Waples holding the horse (Courtesy of Ron Waples)

And off he went to Coldwater. He asked Keith for a job.

"What's your mother and father got to say about this?" Keith asked him. Waples told him he'd left home and needed a job.

"Well, where are you going to stay?" Keith asked.

Waples had that worked out, too. He had an uncle, Percy, who lived nearby. Perc said he could stay at his house.

So Keith told Waples to come in the next morning and "we'll see what goes on."

Ron and Keith Waples. (Photo courtesy of Ron Waples)

You could say the rest is history. Waples had landed in the lap of the most respected horseman in the country, perhaps anywhere. The dominoes all fell in a certain way to lead Waples to a career that put him in the Canadian Horse Racing Hall of Fame in 1986 and the U.S. Hall in 1993, after winning every major race on the continent, including the U.S. pacing Triple Crown (Cane Pace, Little Brown Jug, Messenger Pace.). He also ended up on the Little Brown Jug Wall of Fame in 2006, no doubt because he also picked up a last-minute catch drive on Fake Left, an upset winner in 1992.

When he picked up that catch drive -– regular driver Mickey McNichol was injured in a race earlier in the day -– Waples denied favoured Western Hanover a Triple Crown win. Indeed, the presence of Waples on a race card was powerful enough to change histories. Never mind that he became the first man to win two $1-million races in less than a week when he won the Meadowlands Pace with Ralph Hanover and the Sweetheart Pace with Shannon Fancy in 1983. He had already returned home to Toronto when he got the call to drive the filly and went from having no drive to winning a million-dollar race.

"It's a good thing a lot of things happened," Waples said. "It's a good job Jack Turner was working that day. There are so many ifs. That's what so crazy, and more importantly, that's what is so good about life. Everybody has ifs: If I didn't do this, if I didn't do that. To me, I was one of those lucky people."

And the taciturn Keith? How had he passed on that magic? "He was an exceptional boss," Waples said. "Any little bit of success I've had, I owe it all to Keith and to [Keith's brother] Murray. They put up with me when I was a snotty-nosed kid that landed on their doorstep. They didn't have to do what they did for me."

But Keith was not a teacher. "Never was," Waples said. "Never will be."

"But if you were smart enough not to say too much and just watch what he did, there was a chance you were going to learn something," Waples added. "To this day, I'll watch him when he's around horses. He just has that way with an animal, with a horse. He was just exceptionally good at what he did.

"He worked hard. But he was a good boss and I think he was a fair boss. He didn't want something for nothing. He just wanted a day's work out of you, if he could get it. I'm not sure he got a day's work all the time out of me."

Years later, when he was being inducted into the Canadian Horse Racing Hall of Fame, Waples took special care to thank his cousins for taking him in and teaching him the ropes. And he couldn't resist, with Keith sitting at his table. Out came the words: "I'm not sure that he ever overpaid me."

At the table, Keith didn't even pause between mouthfuls and said: "Geez, I thought I was paying him what he was worth."

Keith always had a way of ensuring that the young Waples never got too big for his boots. One night, when Keith wasn't driving, Waples took the reins and won three races. "I came back to the tack room, and I'm walking this tall," Waples recalled. "I just won three races. You've got to make an appointment to talk to me now. I'm the man, you know."

Keith was sitting in the tack room, having a beer, and talking to somebody else. He hardly paid any attention to the kid. The young Waples didn't know what to say. He couldn't just blurt out: "Hey, what do you think of that?" So he said nothing. Just took his colours off and sat there.

Suddenly, Keith turned to him and said: "Jesus Christ, go out and check them water pails, see if they are dry." It was a big thing with Keith: horses always needed water. The command broke the ice.

Finally, Keith said to his young cousin in understatement: "You had a good night."

But that was fine with Waples. "I don't ever remember him saying I drove bad, or what a shitty drive you gave that one," Waples said. "That was probably more important than patting me on the back."

Waples won his first race with Ferndale Prince at Sunnydale Raceway in North Bay, Ont. He used to joke that he was too small to be a hockey player, and not smart enough to be an accountant. And when he did win, he was known for his selection of bon mots such as: "Better to the needy than the greedy," or "It couldn't have rained in a drier spot."

Friends forever

Sixty years ago, O'Donnell remembers that he first met Waples because they toiled in the same barn on the Greenwood Raceway backstretch. O'Donnell worked for Bill Wellwood while Waples was working for Keith. Waples is four years older than O'Donnell, who never lets him forget it. And they verbally joust, always. They have been for years.

During a two-year-old race at The Meadowlands one time, Waples' colt fell down right in front of O'Donnell, who couldn't avoid him, his wheel running right up over Waples' back. O'Donnell bounced out of his seat, but he got lucky and bounced right back in. Waples wasn't so fortunate.

"I spun him around pretty good," O'Donnell said. Waples was whisked off to the infirmary.

Finally, Waples returned to the drivers' room, where everybody else was sitting, watching television. "Are you okay?" O'Donnell asked.

"What the hell were you doing?" Waples said to O'Donnell. "You had five minutes to miss me."

"Who said I tried to miss you?" O'Donnell countered. And so it goes between the two of them.

O'Donnell had a first-hand account at how driven Waples was, despite his youth. "Nobody worked harder than [Waples]," O'Donnell said. "He worked hard and that was his whole life. He worked hard. Played hard."

On his own

Eventually, Waples went out on his own and yes, it was difficult at first. "It was tough, the same as it is now," he said. "Nobody is going to hand something over to you." But he got lucky after being in business for a year when he plucked Caroldons Knight out of a Pennsylvania sale for $13,000. "He had a bad pair of front legs on him," Waples recalled. Caroldons Knight was one of his first purchases. He was in his early twenties and Caroldons Knight changed his life.

Caroldons Knight proved to be a tough, tough racehorse for Waples. He was the first good horse he had. He put Waples on the map. Caroldons Knight earned more than $280,000, which in those days, was a lot of money.

Waples started winning lots of races, and creating benchmarks for the sport in a way nobody had before him: the first to win more than 300 races in a season (he did this eight years in a row); then the first to win 400; the first to win $1-million in Canada during a single season, and then it became normal for him to drive winners of $2-million in five consecutive years. On and on. O'Donnell got the nickname "Magic" at The Meadowlands for his feats. Waples was much the same. The accolades rolled in. The awards, too.

One of his first helmets –- now well-worn, having lost some of its blue and gold lustre -- still hangs on the wall in his basement. Although Keith had recorded the first 2:00 mile in Canada with Mighty Dudley in 1959, Waples got his first 2:00 mile with one of Keith's top pacers, Blaze Pick in 1968.

Waples fans

Waples loved Greenwood. It had a certain atmosphere. Perhaps it was also because he'd done well there, too. He remembers a woman who used to bet on him all the time and wasn't always enamoured with his defeats. Sometimes, Waples dragged false favourites with him, from folk who always thought he had the edge. And of course, he'd sometimes get beaten on a false favourite, if it had no shot at winning at all. When this happened, the woman would be ready for Waples when he returned to the paddock and would greet him with no small amount of cussing. "You no good! You dirty, rotten SOB! You don't deserve to live!"

Waples would keep on walking, never stopping to talk to her. But sometimes, he'd let fly over his shoulder: "Stick with me, baby. Just stick with me. You'll be all right."

Then he'd win a couple. "Now she wants to adopt you," he said. "She had just wanted to murder you. Now she wants to adopt you."

Greenwood bettors were very hardcore. They took the game very seriously. Some were so hardcore that they would drive all the way to Montreal, and stay for a night to see a race. Even so, Greenwood fans weren't quite as explosive as their counterparts in Montreal, Waples said. The odd time, disgruntled Greenwood bettors would set a trash can or two on fire. Montreal gamblers would riot. Blow things up. Go after the trainers and the drivers.

Waples discovered how dangerous Blue Bonnets Raceway could be when he went there with Keith one year. "Keith had brought a bunch of New Zealand horses over and their lines didn't look any good," Waples said. When they'd win, they'd pay a good buck to the handful who bet on them. It happened more than once. "So now they want to shoot Keith," Waples said.

In the heat of all this, Keith had a suggestion for his young protégé. "How about you parade these horses for the first or second race?" he said to Waples.

"I didn't know any different," Waples said. "They're not after me. They're after him."

But some guy threw a firecracker at Waples. Boom! It crackled in his ears.

Waples hustled back to the paddock. "You parade your own horses!" Waples told Keith. "They ain't shooting me! I don't want no part of this! I'm too young to die!"

Waples spent 20 years racing on the Ontario Jockey Club circuit –- as Woodbine Entertainment Group used to be called –- and closed out Greenwood by winning the last North America Cup there with Presidential Ball in 1993 in track record time. He spent 11 years in New Jersey, returned home in mid-1996, and promptly drove horses to win $1-million by season's end.

Over the years, Waples developed lasting friendships with a wide array of people in the sport. "Everywhere you go, they ask about him," O'Donnell said. "And he's raced everywhere. He was great for the PR part of the business. He always had time for everybody. He was always trying to help the little guy, too. He never forgot where he came from."

Waples drove in Macau. He drove in Sweden, where he became the first North American to win with a coldblood. These horses were a cross between a standardbred and a riding horse, thick-bodied like a washer woman. Waples found his steed particularly difficult. "They are very ignorant horses to drive," he said. "You pull every inch you can with him, because if you give him just a little bit of line, he's going to run."

When he won, Waples was presented with an embroidered hat with a huge red tassel. (Of course, it hangs in his basement.) "If the tassels were on one side, it meant you were married," he said. "If they were on the other side, you weren't. At that point in time, I'm not sure where this tassel should be. So I just let it flop where it flopped."

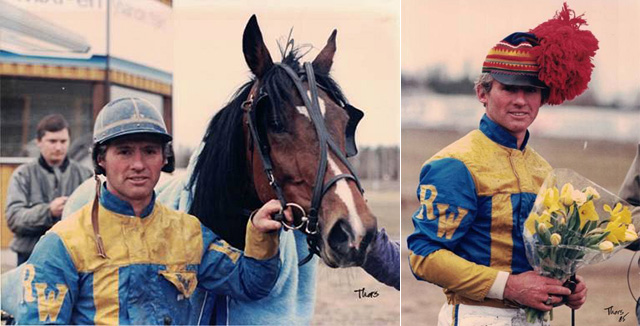

Left: First North American to win with a coldblood trotter. Right: The Swedish hat. (Photos courtesy of Ron Waples)

The most gentlemanly of owners

One of his early owners was Joe Panaro, a 30-year client from Kitchener, Ont., who also became a friend. Waples, Panaro and Marshall Dorion of Collingwood, Ont., formed the W.A.R. Stable. "He was really one of the last true gentlemen," Waples said of Panaro. He steadfastly believed in anything Waples did. His faith was unshakable.

One day, Waples told him he was going to Kentucky to see a trotter he'd like to buy and he asked Panaro if he'd like to come. Panaro was agreeable. Waples drove Panaro's big Chrysler New Yorker.

Panaro had a way of tapping his fingers together when he was nervous. On the ride down, he began to tap his fingers together. Waples wasn't dallying. It was a long trip to Kentucky, after all.

Waples saw his friend lean back, peek at the speedometer, tap his fingers and say: "Do you know something I've noticed, Ronnie?"

"No," Waples replied. "What?"

"They're making these hydro poles a lot closer together all the time," he said.

"So what are you saying?" Waples said. "I'm going too fast, Joe?"

"Well, all I'm saying is that they're making them closer together."

Waples slowed down.

"He was a priceless, priceless man," Waples recalled. "I could go into a bank, rob it, shoot somebody and Joe's interpretation of that would be: ‘If they would have just given him the money, he never would have shot anybody. Just give Ronnie the money. He needed the money'."

Once Waples headed off to Harrisburg to buy some aged horses with $150,000 to spend for Panaro. Waples picked out two horses that he liked, both of which had finished second or third to Niatross, which was no disgrace at all. One of them was called Alba Time. The other, JDs Buck.

Waples figured he had to pick one or the other. The money probably wouldn't cover both. Alba Time "looked like crap." Waples figured he could give him a month off and fatten him up and he'd be as right as rain. Old Buck was the picture of health, although he had bad knees.

Waples clambered his way up to a seat high up in the stands, to think about all of this without distraction. "I got to think this out by myself," he said. A good cigar helped. His decision was tempered by the fact that Alba Time was the first to go into the ring. Waples bought him for $100,000.

He didn't know if he'd bought the right one, but he thought he'd better go down to have a look at him. On the way, he walked past JDs Buck's stall. Old Buck was looking out through the bars of the stall door as if to say: "Pick me! Pick me! Pick me!" Waples heard the call, loud and clear.

Back he went up into the stands, smoking his cigar. When the smoke cleared, he had bought JDs Buck for $160,000.

Sure enough, the numbers didn't add up. "This is great," Waples thought. "I don't know how I'm going to accomplish this. Now I've got to go home and tell Joe what I did."

Back home, he said to Panaro: "Joe, I've got good news and I got some bad news. Which do you want first?"

Panaro opted for the good news first. Waples told him that he had bought a couple of real nice horses.

"Okay, so what is the bad news?" Panaro asked.

"I paid a little bit too much for them, Joe," Waples said. "I'm over the budget."

When Waples told him he'd spent $260,000, Panaro looked at him and said: "My god, Ronnie. That's a lot of money."

"Don't worry, Joe," Waples said. "I'll get it covered at the bank. We'll be all right."

He gave Alba Time some time off and brought him back to the races. By this point, he had two months of work into him. He raced Alba Time two or three times but the horse couldn't beat a hamster on a wheel. "This horse is no good, I'm telling you," Waples told Panaro.

"Ged rid of him, Ronnie," Panaro said. "We don't want them around, if they are no good."

They ran Alba Time back through another sale, and got $20,000 for him.

"It wasn't good, Joe," said Waples, informing him of the result.

"Well, that's not bad," Panaro said, when hearing the amount.

"What do you mean, it's not bad," Waples said. "I give $100,000 for him!"

"Listen," Panaro said. "We saved $20,000. We could have lost the whole thing. We lost only $80,000."

"He could justify anything I did," Waples said.

As for JDs Buck, he more than made up for it, winning about $1-million. He just kept winning.

In fact, within a week of Waples having bought JDs Buck at the sale in Harrisburg, he asked Jim Miller to race him for him in the final Pennsylvania Sires Stake of the season at Liberty Bell before he took him home to Canada. JDs Buck won it and put $20,000 into Waples' coffers before he'd written the cheque to buy him.

Yearling sales

Waples learned a long time ago that things happen for a reason. He once rented an entire Brookledge transport that would carry 14 horses at a time at the Harrisburg sales. He begged and borrowed the money to bankroll the purchase of horses to fill it, and at the end of the day, Waples discovered that although he was tapped out, he had one empty stall on the truck.

He decided that he would nip back into the sale, and pick up something cheap, just to fill the stall. As he strode thought the stable area, he saw a horse walking toward him with a nice head. Waples took a look, found him very correct, if not very big.

He looked at the catalogue and saw the colt was by Big Towner and knew that he wouldn't bring too much, although he wasn't from a bad family. He bought the colt for $4,500. "I don't know where I'm going to get the $4,500," Waples said. "But the truck is full. You've got to cross one bridge at a time."

He took them to Florida and "I trained them things," he said. The colt, called Lustras Big Guy, ended up winning a million dollars. The rest of the truckload didn't earn $200,000 altogether. Waples ended up selling Lustras Big Guy to Bob McIntosh.

Audrey Campbell

For a kid who started out his working life with $32 in his pocket, Waples got to work for clients who had deep pockets and heritage and breeding and all of that. Waples brought his forthright candor to the relationships. And it seemed to help him greatly.

He met Audrey Campbell, the daughter of Roy Thomson, alias Lord Thomson of Fleet, a media mogul who created such an empire that he and his family became the richest in Canada. He first heard the name when Dr. Glen Brown tapped Waples on the shoulder one day and told him that there was a woman who wanted to get into standardbreds. And Brown had recommended Waples to her.

"Would you want to meet with her?" Doc Brown said.

Waples' first question: "Does she have money to pay?"

"Yes, she definitely has money to pay," Brown said. "I think this will be worth your while."

Waples first talked to her on the phone. Campbell told her she had a yearling that her daughter, Susan Grange, had purchased. "She picked this mare out for me, and I'd like you to train her for me. And I've got a set of harness, too," she said.

Grange is a major figure in the show-jumping world. At the time, she rode hunters and jumpers. Now she owns Olympic show-jumping horses ridden by Canadian icon Ian Millar and Conor Swail of Ireland and operates Lothlorien Farms near Caledon, Ont.

When the yearling bunked up in Waples' barn, he wasn't impressed. "This thing should be skidding logs, right off the bat," he thought. He had it for two weeks and finally told Campbell: "We're going to have to do something different here."

"What?" she said.

"You have to give this horse to somebody else," Waples told her. "I ain't wasting your money and my time because it's not worth it."

"What will I do with him?" Campbell asked.

"Give it away. It's the best thing," he said.

"What will I do with the harness?" she said.

"The harness is crappy, too. Give it away, too. I don't know who bought you the harness, but it's a crappy set of harness."

It was the start of a beautiful relationship. "We just hit it off good," Waples said.

One horse that Waples bought for Campbell was Rank Hanover, and he had talent. He paid $150,000 for him as a yearling -– the most expensive yearling he'd ever bought in his life. Waples raced him five times, the horse earned $150,000, and broke his leg. "Who said life is easy?" Waples said.

Eventually, Campbell also owned part of Armbro Dallas, too. His claim to fame was handing Nihilator only the third defeat of his career to that point in the Pilgrim Stakes in November of 1985.

Waples purchased Armbro Dallas, a son of Abercrombie, as a yearling for $30,000 and sent him to Florida to friend Archie McNeil to teach him his early lessons. In the spring, Waples went to Florida to train them. McNeil asked him: Which one do you like the best?"

Waples liked Armbro Dallas the best. McNeil liked a Meadow Skipper colt, whose name was Witsends Wizard.

"No, you're wrong Arch," Waples said.

"I'm telling you, that little horse [Armbro Dallas] is a nice little horse, but I think he'll just fall apart," McNeil told him.

"Nope," Waples countered. "You've got the wrong one, Arch."

Come spring, as the colts were heading north, Waples asked McNeil how he would price Armbro Dallas, in the event somebody wanted to buy him. Archie didn't really know, but spit out $75,000. "He's sound," he said. "But he's not that big."

So Waples told McNeil he would offer him a quarter interest in the colt, at the purchase price of $30, because he'd never given him a bonus for training his yearlings. But McNeil didn't have the money. Horsemen are notoriously short of cash in the spring after buying and training yearlings that haven't raced yet.

"Come spring, I'm always broke," McNeil said.

So Waples promised to send McNeil the bill for his share only when the colt started to make money.

Armbro Dallas earned $118,000 as a two-year-old. McNeil was happy.

The following year, McNeil wanted to put him in a two-year-old sale, because he wanted the money to buy a farm.

"Geez, Arch, he's sound as a nut," Waples said. "I look for horses like this all the time. I don't want to sell him."

The two agreed that he might be worth $130,000 to $150,000 at this point. Waples had Campbell in mind. "I know this is not something you asked for," Waples told her. "You wanted yearlings, but I got something here that maybe you should look at."

He told her a quarter interest in Armbro Dallas would cost her $37,500. "You must really like the colt," Campbell said.

"He's a helluva nice horse and he's as sound as a nut," Waples said.

Campbell was in.

Armbro Dallas earned $1.4-million in his career. "Everybody that owned the horse made money off him," Waples said.

Waples as a driver

When Armbro Dallas defeated Nihilator, he paid $70 for a $2 win ticket. "[Waples] never had the best horse," O'Donnell recalled years later. "But he always paid a big price when he won them big races, you know."

"He was always in the right place with them and he didn't over race them and he took advantage," O'Donnell said. "I think he took advantage of other people making mistakes. And it worked for him for a long, long time.

"He had a tremendous set of hands. He was quiet with a horse, but he always had the horse under his control. Very, very good at it. I've seen him do some amazing things over the years. I've seen him do some stupid things, too, but we won't talk about that."

Waples always had a strategy when he raced at The Meadowlands. At the time, O'Donnell and John Campbell always got the best horses to drive. "Why not just get close to them?" Waples reasoned. "Maybe follow along and get a cheque.

"I always watched what people did," Waples said. "I was really interested in what was going on in the race."

"It was a beautiful thing to see him in a race," said veteran Steve Condren. "If you ever had an outside post, you'd want Ronnie Waples to drive. He just had a knack for getting the most out of a horse. He's proven it over the years."

Waples always maintains that a good horse makes a good driver. But he learned very early that he had to get a horse to relax to get the most out of them. "He can't be on the iron all the time," Waples said.

A cursory look at some old replays shows that Waples was the first guy on the gate, but he'd quickly drop the lines. He's seen drivers put their horses' noses on the gate, but pull back fiercely as they do it. "You're defeating your purpose," Waples said. "I just found if they relax, and that gate says go, I've got two choices: go forward or hang to the left. For me, that worked good."

He has his favourites. He's impressed with Scott Zeron. He once told Zeron's father that: "if [Scott] keeps his nose clean and keeps his feet on the ground, he's going to make you and I look like amateurs." He really likes James MacDonald, who he says has a great set of hands. Jonathan Drury is "just a hard go-getter." And Doug McNair "can get a lot of speed" out of horses, Waples says.

He remembers Jack Moiseyev when he started in New Jersey. Waples gave him the odd horse to drive because "I was impressed with how quiet he was on the lines," Waples said. And David Miller, when he got started, same thing. So quiet on the lines.

The sons of Ron Waples

With two of Waples' sons -- Ronnie Jr. and Randy -- started to drive, he followed Keith's lead. He didn't say much. The only thing he would say is that this horse likes to be on the gate, the other one doesn't. This one doesn't mind being first up. This horse doesn't want to be first up. "And that's all you can say, because when that gate says go, you've got a fraction of a second to make up your mind," Waples reasoned. "If you pick the wrong one, you just go to the shitter."

Neither son showed an interest in racing until they were 12 or 13. When they turned 13, Waples got them a $2,000 claimer that raced at Orangeville. He told them to train her the way they saw fit. She made a few bucks for the brothers.

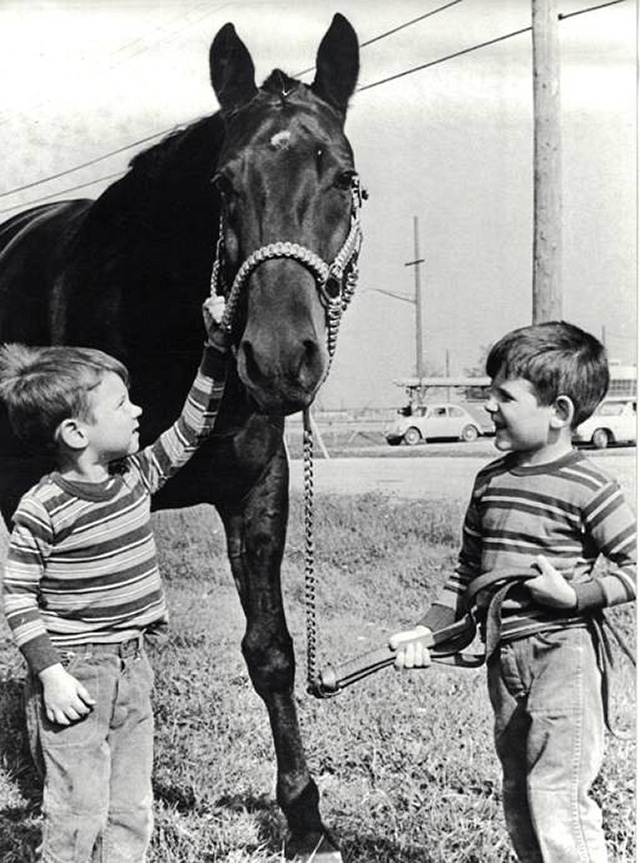

Randy Waples, left, and Ronnie Waples Jr., right, with Perfect Time. (Photo courtesy of Ron Waples)

Waples never pushed them toward a career in racing, either. He used to coach them playing hockey but he had rules: They had to give 100 per cent, particularly because Waples had to get up at as early as 5:00 a.m. to get them to the rink on a Sunday morning, after racing Saturday night. "I don't care whether you score a goal or not," he told them. "I don't care what happens, but you have to give 100 per cent.

"Because if you are lackadaisical, dad's not going to get up in the morning."

But both eventually drifted toward racing. Ron Jr. became known as the trainer of No Sex Please, a splendid trotter that won the Maple Leaf Trot three times, the Breeders' Crown twice, set two world records and earned just shy of $2 million in his career. Randy has become a powerhouse on the Woodbine-Mohawk circuit, with more than 6,300 wins himself. Another son, Matt, at age 15 became the youngest to win a Sovereign Award for photography in 2009. He's now pursuing this passion in university.

A daughter, Meghan, is in her fourth year of medical college in Lexington, Ky., but a couple of years ago, worked alongside her father and Gregg McNair one summer with the horses. A hard worker, she's a straight-A student. Says her brother, Randy: "If you totalled up all our marks in school [Randy, Ron Jr. and Ron Sr.], they still wouldn't add up to hers."

Waples told his driving sons that it never hurts to slip a horse up on the inside during a race. Suddenly, a hole might open up. "I won a lot of races that way," Waples said. "Just lo and behold."

Ringing the Bell

He won the 1988 Kentucky Futurity that way with longshot Huggie Hanover. In both heats, he never left the rail. Huggie Hanover was such a rank outsider –- he was 60 to 1 in the first heat -- that Waples told the owners not to come. But he won that first heat over top colt Supergill. And when he won the second heat, he tied the stakes record of 1:55.

Waples worked hard for that surprising win. When he warmed up Huggie Hanover for the first heat, he didn't warm up well at all. "I mean, terrible," Waples said. He told the groom, Karen Cooper, to get the horse over to the blacksmith and have him pull all of his shoes.

"Do you mean his hind ones?" she asked.

"No, I mean, all of them," Waples said. "He's no good, Karen, I'm telling you."

"You can't pull them all off," she said.

"Yes I can," Waples said. "The blacksmith can. Take him over there."

So over he went.

At the time, Waples started chatting with the Red Mile paddock judge, Bobby Owens. Waples noticed a bell just outside the paddock. Owens would ring it to tell the horses to come out of the paddock.

"Gee, you got your old bell looking good," Waples said.

"Do you want me to tell you a funny story about that bell?" Owens said.

"Yeah," Waples said, intrigued.

"The number of people that have rang that bell that have won the Kentucky Futurity is unbelievable," Owens said.

This struck a chord. After all, every little bit helps. "Bobby, I want to ring that bell," Waples said.

"You got it," he said.

So Waples rang the bell, ran downstairs and won the first heat.

Immediately afterward, Waples ran back up and told Owens: "Bobby, don't let nobody else touch that bell." He rang the bell again. Huggie Hanover won the second heat.

"It was just so crazy," Waples said.

"He was a nice horse, but he wasn't a great horse. He was good on the right day." And the bell helped too.

Driving a quality trotter

Waples did get a chance to drive a really good trotter after another bout of honesty with a major figure in the sport. He took on John Simpson, the proprietor of Hanover Shoe Farm in 1985 and had an animated discussion, a disagreement with him. Del Miller heard it all.

The next day, Waples told Del Miller that he felt he'd been a "little yappy," to Simpson, although he hadn't shouted at him, nor was he impolite. He was definitely stressing a point.

"No you weren't," Miller said. "You had a good valid point. And let me tell you, he'll only respect you for it."

The next year, Waples drove all of Simpson's good horses, Sugarcane Hanover included. Waples loved Sugarcane Hanover, winner of the Breeders' Crown in 1986, defeating favoured Royal Prestige. Waples was never defeated with Sugarcane Hanover. That week, Waples scored a Breeders' Crown hat-trick, winning also with Glow Softly and Super Flora.

"He was a good horse," Waples said. "He was one of the nicest trotters I ever drove in my life. Couldn't leave the gate much, but I tell you, when you take him out of the hole, he went 100 miles an hour in three steps. Just come out of the hole like a pacer." He eventually was sold to Sweden for $2-million, and when he returned to the United States, he won the March of Dimes Trot at Garden State Park, defeating two great trotters: Mack Lobell and Ourasi.

Waples also won the Hambletonian with Park Avenue Joe (in a dead heat) during the 10 years he was stabled at The Meadowlands. Waples got the drive because John Campbell, who had driven both Park Avenue Joe and Peace Corps, had gone for Peace Corps, a filly that had won 17 consecutive races. The Hambletonian marked the first time she had raced against colts. The race was to have been a pitched battle between Peace Crops and Valley Victory. But Valley Victory had a viral infection and didn't start.

Waples had never driven Park Avenue Joe before. "It was a nice time to get up," he said. Park Avenue Joe and longshot Probe finished in a dead heat in a race-off, but Park Avenue Joe was awarded the win on the basis of a better record in the first two heats.

Ralph Hanover close to the heart

But of all the horses that Waples ever drove, Ralph Hanover occupies a special place. "He was my Niatross," he said. He still has the whip he carried when he won the 1983 U.S. Pacing Triple Crown with Ralph Hanover.

The trail they blazed through all of the major races that year on the continent was a like a party, particularly since Waples owned the horse in partnership with his friends Dick Dinner and Norm Keyes, who worked the scene like a comedy act, tossing insults that hinted at their affection for each other. Together, they ran the Grants Direct Mailing Service. They also owned Huggie Hanover.

"They were super," Waples said. "Not only were they great owners, but they were fans of the industry. Not only were they fans of mine, but they were fans of anybody else that got a good horse or that was doing good. They were really good people."

The two had names for each other: the blind man and the fat Christian.

Dinner had such extremely poor eyesight that he'd read the racing program with the page only inches from his face. Delicacies were not needed in dealing with him. Waples would tell him not to leave nose prints on the program.

Dinner dubbed his friend, Keyes, "the fat Christian" because of his lofty position in his church. "You should see him when he gets his robe on, Ronnie," Dinner would say. "We're all going to go down there and watch him when he gets his robe on, and gets up there, blessing these people."

"Oh god, I don't want to hear this Dick," Keyes would say.

"Ronnie, you and I are going to go down there, when Himself gets his dress on," Dinner would say, paying no attention.

"You pair of [bleep] Protestant [bleepety-bleeps]," Keyes would reply. "They're not going to let you in the front door."

All was well in this atmosphere.

At one time, the threesome went to Liberty Bell to buy a trotting filly. At the time, the sale was held in a barn area with very poor lighting. "You could hardly see the damned horses," Waples said. Worse still, the sales were held at night.

When Waples checked out the stock, he couldn't find a trotting filly he liked at all.

"You've got to find one," Keyes said.

"I know Norm, but I seen a pacing colt I like."

"Oh geez no," Keyes said. "The blind man will never go for a pacing colt."

"Yeah, but Norm," Waples said. "This is a nice colt. He's was by a helluva horse from Montreal and I think he's going to be a sire."

Waples had a plan. They'd get a six-pack of beer, give a couple to the blind man, and take him through the dim barns. "We'll show him the horse," Waples said. "He ain't going to be able to see what it is. We'll just tell him it's a trotting colt."

Dinner had the program, up to his eyes. He was in the dark.

"Pretty damned good-looking colt, Dick, I'm telling you," Waples said. "This one is all right."

But Dinner was not at all fooled. He knew the colt was a pacer. Suddenly, he said in a loud voice, (which is how he talked): "Norm! Norm! We can't buy him. He's got ball bearings [testicles]. Norm! We don't want this one. No! No!"

"Now listen Richard," Keyes said. "Ronnie says we buy this colt, if the colt don't turn out, he'll never ask us to buy another pacing colt. We'll just stick with trotting fillies."

"Oh god," Dinner said. "How much are we going to go?"

Waples thought $35,000 to $40,000. The colt came into the ring and Dinner and Keyes were out behind the auction stand, where it was rather dark, too. Keyes did the bidding and when the bid reached $35,000, Richard threw himself in front of his partner and began a loud protest.

"Norm!" he cried. "We don't want him! He's got ball bearings!" He's shouting and everyone can hear. Keyes continued to bid over his head.

They bought the colt for, say, $45,000.

Dinner was such that he didn't whine once the deed was done. But it didn't stop him from endlessly needling Waples, especially when the colt turned out to be slower than a two-toed sloth. In front of everybody, Dinner would say: "Our astute trainer here, Sir Ronald, bought this pacing colt. We were looking for a trotting filly, but Sir Ronald buys this pacing colt, ball bearings and all. And they flogged us to the tune of $45,000 and we kept and trained him for a year. And then we flogged some poor guy from Nova Scotia for $700. Flogged that poor guy."

"Dick would put such a twist to it," Waples said.

Of course, that wasn't the end of their adventures. Waples and Dinner headed back to their hotel after a night at the races one time, when Dinner said: "Sir Ronald, we'll go down and have a beer."

But Waples had been doing a lot of travelling at the time. He was exhausted. "I got to go to bed," Waples told him. "I'm just done."

In bed, Waples couldn't sleep. "What am I going to do now?" he thought. So he dialled Dinner's room and said: "Let's go for a beer. I can't go to sleep."

"All right, Sir Ronald," Dinner said. "I have to get dressed. I'm in my birthday suit."

Too much information. Visuals, you know.

Downstairs they went at 1 a.m. Eventually, the two Canadians asked the waitress if they could take a six-pack back to their rooms. No, they couldn't, but they could take glasses of beer. So each loaded up with three tall glasses of beer, cupping them in their hands. All was well until they came to the elevator.

"Dick, we've got a bit of a problem," Waples said. "How are we going to push the button for the elevator? I don't want to set these beers down. I'm not sure I'd get them back up in my hands."

"Sir Ronald," Dinner replied. "The good lord put this beak on me for a reason. Step aside, Sir Ronald. Step aside."

Dinner used his ample nose to press the button. "It was the funniest thing I ever seen," Waples said.

They all crossed paths again in 1981 when Waples thought enough of a Meadow Skipper yearling called Ralph Hanover to bid him up to $40,000 in the ring. "That's enough," Waples said to himself. "I didn't look at him that close."

But as he turned, he saw trainer Stew Firlotte, also looking at the colt.

"Did you like that colt?" Firlotte asked Waples. Waples told him he did like him but hadn't had a close enough look. Had Firlotte?

Firlotte had. "He's all right," Firlotte said. On the spot, they hatched a plan to buy him together. And they did. Waples told Firlotte that he may as well take the colt down to Florida and train him. "If you own a piece of him, there's no sense in me training him up here," Waples said.

Firlotte said he'd take two-thirds of the colt, and Waples could have a third. "Okay," Waples said. "I don't care."

Two or three weeks later, Firlotte confessed he had overspent at the sale, and asked Waples to take two-thirds. "Sure," Waples said. "I don't care."

Sometime after that, out to lunch with Dinner and Keyes, Waples heard Keyes suddenly said out of the blue that he wished he had bought another pacing colt that year.

"Hey," Waples said. "I got something you might be interested in." He told him all about Ralph Hanover, but admitted to Keyes that he was taking Firlotte at his word, that the colt was doing well in Florida.

"What do you want for him?" Keyes asked. Waples said he'd sell them a third of the horse for exactly what he had invested in him when he stepped out of the auction sale until that day. No more. No less.

A day later, Dinner and Keyes were part-owners of Ralph Hanover, with the only stipulation that the colt stay in Firlotte's care, and Waples would drive him. "That's good enough," Keyes said.

"That's how Norm and Dick got him," Waples said. "Things happen for a reason."

Ralph Hanover ended up winning $1.8-million in his career. As a three-year-old, he won $1,711,990, a single season's earning record for a standardbred at the time. He kept winning and winning, 20 races in 25 starts, with four seconds. Not only did he become pacing's seventh Triple Crown winner, but he scored victories in the Queen City Stakes (now called the North America Cup), the Meadowlands Pace, the Prix d'Ete, and the Adios Stakes. He set a world record for a three-year-old pacing colt on a five-eighths mile track (1:54) and set the fastest mile ever on a half-mile track (1:55 3/5).

Ralph Hanover was perfect to drive, Waples said. "He was so good, he made me look good. He just one of those horses you could race with no handholds. Very responsive."

At age 28, Ralph Hanover was euthanized on Oct. 18, 2008. Sadly, the memories surrounding this little Canadian juggernaut team are fading. Dinner died on Dec. 9, 2014 at age 85. Keyes followed in March of this year at age 86. Firlotte died on Aug. 15, 2012 at age 72.

Left: Waples and Ralph Hanover. Right: Waples and Ralph Hanover, both with a few more gray hairs. (Photos courtesy of Ron Waples)

A life well lived

Still, Waples is very much alive. (His cousin, Keith is 92, still going strong.) And Waples still has lots of spunk. Once Chris Christoforou Sr. found all of his jogging carts on top of the roof of a barn. Waples may have had something to do with that. And, so we're told, he once managed to leave a goat in the judge's office.

"There's no factual proof of that," Waples said.

He hasn't lost that rebel nature. "He could catch just as good as he could pitch," O'Donnell said. He wasn't one of those guys, that if you did something back to him, he'd [be sorely miffed.] He got a kick out of it, too."

Waples feels a sense of responsibility to set young folk on their way, to go to school, to follow a path. Sheer luck kept Waples from feeling short-changed in life. Still, he does it with a glint in his eye. Talking to young children, he'd speak to them as if he knew their teacher.

"What's your teacher's name?" Waples asked one little boy. When the boy told him, Waples replied ominously: "My god, I know your teacher. I met him at the laundromat the other day. You got yourself in a little bit of trouble about a week or so ago, didn't you?"

"It wasn't my fault!" the boy cried.

Waples signed many autographs for kids and he got so that he could focus on the kid in front of him, asking questions, listening to explanations, but he would already be zeroing in on the next in line.

One little girl in line must have been told by her mother that Ron Waples, the man signing autographs, was famous.

"But mom," the girl said in a loud voice. "I thought you had to be dead to be famous!"

"I loved it," Waples said. "I thought that was the funniest thing I ever heard."

If there is a positive thinker, it is Waples. And he's now enjoying life. He and Liz travel south in a motor home –- ironically awash in Waples' colours –- because he found the Canadian winters brutal. They've been to Nashville, Memphis, Branson, Arkansas, New Orleans, Florida, trailing along their Kentucky-bred cat, Jack, who once locked them out of the home by standing on the lock button. ("Can I sell you a cat?" Waples says.)

When Liz would work for people like Carl Jamieson in Florida, she'd ask her husband if he had looked for a job, too.

"Yup," Waples would answer. "I opened the bus door and seen a couple of clouds. Didn't see no job." He did, however, work this past winter.

He remembers some golden moments, like Bill Haughton giving him the chance to train Nihilator (Waples owned a share in him) after he retired. Waples just wanted to understand why the horse was so fast. He went a slow mile with him at Garden State Park, and found the horse didn't have much of a gait to him at all when he was going that speed. But Waples let him pace a final quarter in about 29 seconds, really let him roll.

"And the faster he went, the lower his ass got," Waples said. "And the faster he went, the further out he reached. That's the only conclusion I could come up with." Keith had a horse like that, too. Keith predicted this horse, called Laurel Adios, would be good someday, but he was choppy when he jogged.

"You have to tell me why you think this is going to be a good horse," Waples told him. He's got no gait."

(Typically) Keith said: "You just watch and see."

"But that's the way he got," Waples said. "The faster he went, the more he reached out and the smoother he got." He ended up being a good preferred horse.

Waples has also tried cutting horses. Woodbine's leading jockey, Eurica Rosa da Silva, is often a dinner guest at the Waples household. And many years ago, Waples met Avelino Gomez, the jockey who died in 1980 after an accident in the Canadian Oaks at Woodbine. He knew Gomez when he had retired from riding and was training horses.

"Avelino was colourful," Waples said. "For some unknown reason, he took a liking to me. Every time I went, he was always good to me." Because of Gomez, Waples wanted to break a thoroughbred from the gate, just to see what it was like. At the time, Waples was probably 120 to 130 pounds.

"I had it set up one time that I was going to ride one of those horses out of the gate," Waples said. "I wanted to ride one in the worst way. I said I would even buy a cheap claimer if I have to."

Gomez would tell him: "You get a hold of the mane, Ronnie, both hands. Don't worry about the reins. Both hands. Hang on for your life!"

"The more he would talk to me, the more I wanted to do it," Waples said. But insurance issues scuttled that plan.

"I've led a very sheltered life," Waples joked.

Looking back on his life, Waples counts himself a very lucky man. When he talks to younger drivers going through hard times, feeling bad, not doing well, he has one piece of advice for them. "Ever wonder why I kept going all those years?" he would ask them.

"When I got beat, and I felt like crap, I used to say to myself: ‘I'm only one win away from happiness at all times'."

Wonderful story. Should be a

Wonderful story. Should be a shoo in for a Hervey award.

Mr. Thomas you are right

Mr. Thomas you are right however I'm pretty sure there are a few stories that probably shouldn't be shared. Mr.Waples (yes I still call him that) although he says call me Ronnie was a guy I was totally in awe of during my much younger days. Yes he did jog/train horses in the morning in winter at Greenwood without gloves and I know I couldn't. He called me out after a race in the paddock one summer night, who was I to question him some punk kid with a big yap and zero racing resume, I still remember that and he was right. A few years later you don't know what an honour it was for me to have a cocktail or three after qualifiers (and many other occasions) with him and Bill James in Bill's "office" along with other assorted icons of the sport and couldn't have been treated better. I still remember those days like the time we had a few and decided to go out for a few more, no problem races were 5 hours away, I had the night off Ronnie had at least 6 drives so I figured this would be ok.

Well oh wait I don't think I can tell what happened with that big old aircraft carrier of a car we were in since I promised. Needless to say I didn't see a race that night out like a light and next day heard Ronnie won I think 4 or 5. A true hall of famer how we all miss those days.

Ron should write a book (or

Ron should write a book (or has he already?) . A look back when...